The £2,000 Knife Crime

There is a crime scene in your kitchen every Sunday. It happens at the carvery deck or the pass. You bought a beautiful 10kg joint. You cooked it perfectly (slow and low). Then, a chef with a blunt knife and bad technique steps up. They hack. They saw. They cut thick, uneven wedges. They shred the meat.

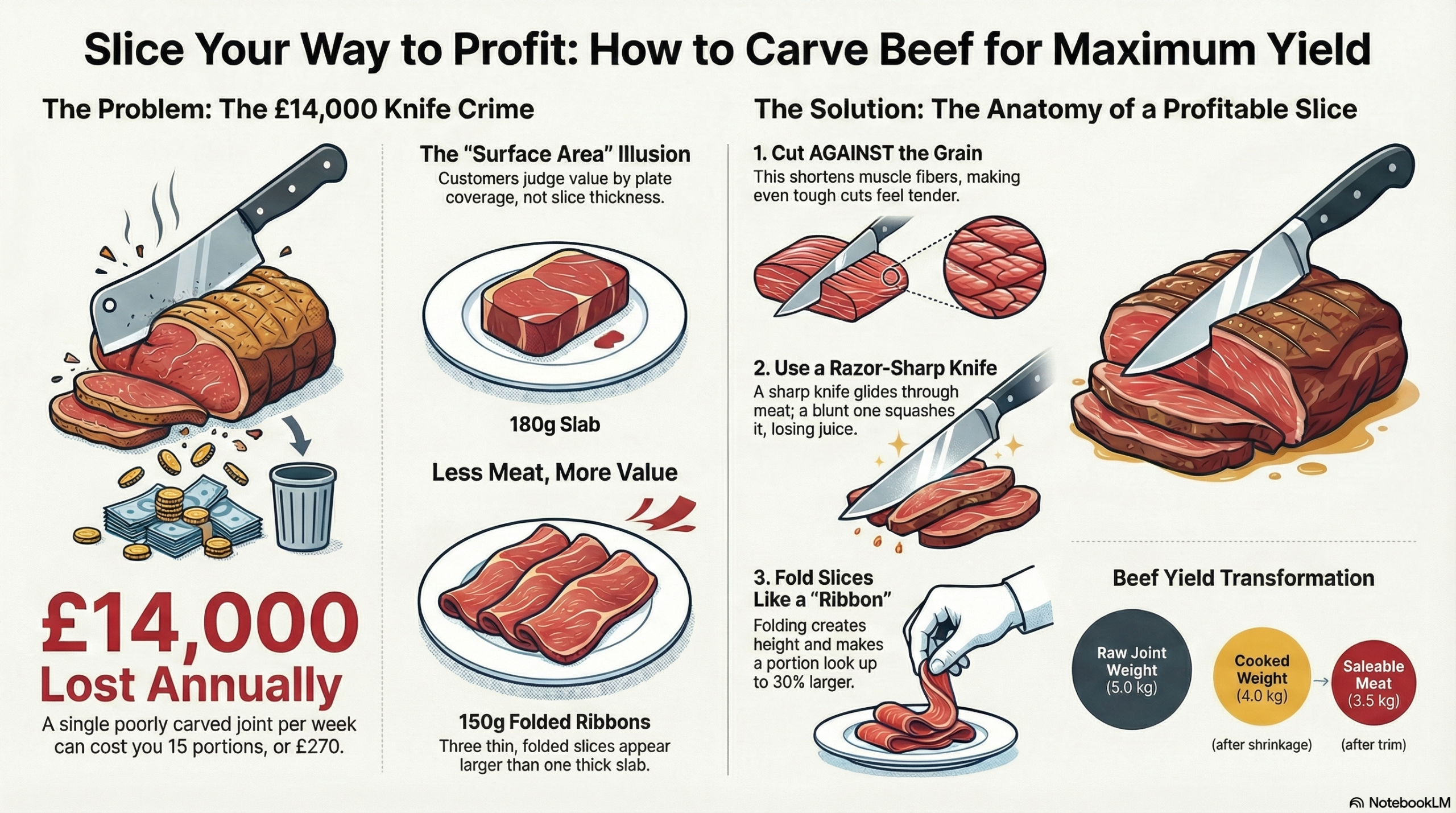

By the end of the service, that 10kg joint—which should have yielded 60 portions—only yielded 45. You lost 15 portions. At £18 a head, that is £270 of revenue lost from one single joint. Multiply that by 52 Sundays a year. That is a £14,000 loss. Purely because your chef doesn’t know how to carve.

Carving isn’t just about presentation. It is the final checkpoint of your margin control.

The £2,000 Knife Crime

How Bad Carving Decimates Your Sunday Roast Profit

There is a crime scene in your kitchen every Sunday.

You cooked a beautiful 10kg joint perfectly (slow and low). Then, a chef with a blunt knife and bad technique steps up. They hack. They saw. They cut thick, uneven wedges. They shred the meat.

The Cost of Poor Yield:

That 10kg joint—which should have yielded 60 portions—only yielded 45. You lost 15 portions. At £18 a head, that is £270 of revenue lost from one single joint. Multiply that by 52 Sundays a year. That is a **£14,000 loss**.

Carving isn’t just about presentation. It is the final checkpoint of your margin control.

The Philosophy: The “Surface Area” Illusion

Applying Rory Sutherland’s principles of perception are critical here. The customer does not weigh the meat. They scan the meat. They judge “value” by how much of the plate the meat covers (Surface Area), not by how thick it is (Volume).

Scenario A (Low Yield/High Volume)

One thick, 180g slab of beef. It looks small. It looks tough.

Scenario B (High Yield/High Surface Area)

Three thin, 50g slices of beef, folded over. Total weight: 150g. Looks bigger, uses less meat.

Carving for yield is about maximizing the visual impact of every gram.

The Tactics: The Anatomy of a Slice

1. Against the Grain (The Golden Rule)

Muscle fibres run in long strands. The Fix: Cut across the grain (perpendicular). You shorten the fibres. This makes even a cheaper cut (Topside) feel tender. Visual: Look for the lines running through the meat. Turn the meat 90 degrees. Slice.

2. The Knife Maintenance

You cannot carve thin slices with a blunt knife. Force squashes the meat, squeezing out the juice (profit). The Fix: The carving knife should be the sharpest tool in the building. It should be honed on a steel every 10 cuts.

3. The “Ribbon” Fold

If you slice thin, the meat can look flat. The Tactic: Pick up the slice and let it fold naturally (like a ribbon) as you place it. This creates “height.” Height = Volume. It allows air under the slice, making the portion look 30% larger.

4. Machine vs. Hand (The High Volume Debate)

For 300+ covers, hand carving is inconsistent. The Tactic: Use a gravity-fed slicer for wafer-thin consistency. Hand-finish the plate by fluffing the slices up. Warning: Ensure the meat is pink and juicy, not grey and dry, to avoid looking “processed.”

5. The End Pieces (The “Chef’s Tax”)

The dried-out end piece is unsellable as a prime slice. The Tactic: Don’t bin it. Don’t let the chef eat it. Dice it immediately for Monday’s Pie Mix or Beef Hash. Every gram has a destination.

The Software Pitch: The “Yield Factor”

Most chefs think a 5kg raw joint equals 5kg of saleable meat. Physics says otherwise. You must calculate based on the *Saleable Meat* after shrinkage, trim, and carving loss, not the Raw Weight.

You need the Roast Forecaster.

This tool does the “Real World” math for you. It tells you: “From this joint, you will get exactly 22 portions IF you carve at 160g.” It is your digital auditor at the pass—if the machine says 22 and you served 18, you know your chef is carving too thick.

👉 Get the Roast Forecaster ToolThe Philosophy: The “Surface Area” Illusion

Rory Sutherland’s principles of perception are critical here. The customer does not weigh the meat. They scan the meat. They judge “value” by how much of the plate the meat covers (Surface Area), not by how thick it is (Volume).

- Scenario A: One thick, 180g slab of beef. It looks small. It looks tough.

- Scenario B: Three thin, 50g slices of beef, folded over each other. Total weight: 150g.

Scenario B uses less meat (saving you money) but looks bigger (pleasing the customer). It covers more of the plate. It looks delicate and appetizing. Carving for yield is about maximizing the visual impact of every gram.

The Tactics: The Anatomy of a Slice

Put down the serrated bread knife. Here is how to carve for profit.

1. Against the Grain (The Golden Rule) Muscle fibres run in long strands (like a bundle of cables).

- The Mistake: Cutting with the grain (parallel to fibres). You get long, stringy, chewy strands.

- The Fix: Cut across the grain (perpendicular). You shorten the fibres. This makes even a cheaper cut (Topside) feel tender.

- Visual: Look for the lines running through the meat. Turn the meat 90 degrees. Slice.

2. The Knife Maintenance You cannot carve thin slices with a blunt knife. A blunt knife requires force. Force squashes the meat, squeezing out the juice (profit).

- The Fix: The carving knife should be the sharpest tool in the building. It should be honed on a steel every 10 cuts. It should glide through the beef like it’s butter.

3. The “Ribbon” Fold If you slice thin, the meat can look flat on the plate.

- The Tactic: Do not lay the slice flat. Pick it up and let it fold naturally (like a ribbon) as you place it.

- This creates “height.” Height = Volume. It allows air under the slice, making the portion look 30% larger than it is.

4. Machine vs. Hand (The High Volume Debate) If you are doing 300+ covers, hand carving is inconsistent. Chef A cuts 150g. Chef B cuts 200g.

- The Tactic: Use a gravity-fed slicer for consistency, but intervene with presentation.

- Slice the beef on the machine to get the perfect wafer-thin yield.

- But do not just stack it. Hand-finish the plate. Fluff the slices up.

- Warning: Machine slicing can look “processed” if not careful. Ensure the meat is pink and juicy, not grey and dry.

5. The End Pieces (The “Chef’s Tax”) The dried-out end piece of a roast is unsellable as a prime slice.

- The Tactic: Don’t bin it. Don’t let the chef eat it.

- Dice it immediately for Monday’s Pie Mix or Beef Hash. Every gram has a destination.

The Software Pitch: The “Yield Factor”

Most chefs think a 5kg joint equals 5kg of meat. Physics says otherwise.

- Raw Weight: 5kg

- Cooked Weight (Shrinkage): 4kg

- Trim/Waste (Fat/Ends): 0.5kg

- Saleable Meat: 3.5kg.

If you calculate your portion cost based on 5kg, you are bankrupt. You must calculate based on 3.5kg.

You need the Roast Forecaster.

This tool does the “Real World” math for you.

- It factors in the Carving Loss (the crumbs, the juice on the board).

- It tells you: “From this joint, you will get exactly 22 portions IF you carve at 160g.”

- It gives you a target. You count the plates. If the machine says 22 and you only served 18, you know your chef is carving too thick.

It is your digital auditor at the pass.

👉 Get the tool here: https://smartpubtools.com/sunday-roast-forecaster/

The Conclusion

The knife is the steering wheel of your Sunday profit. Steer it carefully. Slice thin. Slice against the grain. And remember: You are selling the experience of a roast, not a brick of protein.